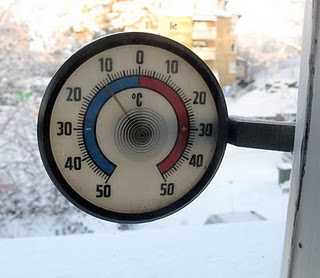

Winter in Sweden, and that means darkness, cold, and snow covering all and everything. No wonder every window is lit, day and night, with glowing stars, moons, snowflakes, menorahs, or the new fashion little reindeer or bears lit by led from inside. Without all those warming winter lights darkness would bend our backs, and we would get swept away by depression. Or maybe not.

Nevertheless, I would like to take this window view to remind myself of another northern glowlight, recently named Dano flagrans. It is a little fish from warmer waters. From where it hails, however, you can actually view the snow of the eastern outcrops of the Himalayas. It is certainly the most septentrional of the Myanmar Danio, but rivalled, apparently defeated in northerliness by Danio dangila which occurs in the Brahmaputra basin in India up to the Dibru River. No other species of Danio reaches so far north.

The scientific history of Danio flagrans begins in 1988, when I, in the company of Ralf Britz and our guide Thein Win arrived in Putao, the northernmost major city in Myanmar. Putao is close to the Chinese and Indian borders, on hills forming the headwaters of the Mali Hka, major tributary of the Ayeyarwaddy River which then runs through Myanmar as one big muddy aorta. Up in the Mali Hka, however, the water is clear, at least in the dry season, not very deep, and the river beds paved with stones and rocks. The fish fauna of northern Myanmar mountain streams is little known. Transportation in the area is relatively complicated, and a lot remains to be done up there in terms of ichthyological exploration.

Back to our story, our little team was quartered in the military camp and we immediately set out to fish, having only two full days at disposal. The Mali Hka itself was too big for fishing, although alright for sightseeing, but around the regiment there were several small streams with low water and convenient for seine and handnets. The streams were shallow, the water was clear, rather cool, and fish were plenty. Here we found Badis pyema which was promptly described already in 2002, and Puntius tiantian in 2005, but other fish have lasted longer to be worked up. Walking along one of the streams, we switched direction to follow a tickle of water, almost no water, coming down the left bank hill, and in there were little skittish fish, almost invisible against the beige earth and seen only as moving shadows. A number of them, certainly Danio choprae – such was the field identification – came into formalin and one made it to a tube of alcohol. Neither Ralf nor I was into danios at the time, so the fish we just hoped would be useful for Fang, and we went on happily, catching Badis pyema and similar fish that had more of our attention those days.

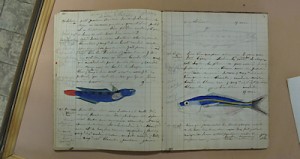

Fresh collected northern glowlight danio, Putao 1998

One of the Putao danios was photographed but this was in times of film photography, with no immediate quality check, and much is to be regretted by the quality of the shot. Publishable it is not, but here it can be showed off as the first image ever taken of a Danio flagrans. The alcohol specimen was sequenced and appeared in a phylogenetic tree as Danio choprae (Fang et al., 2009), and by that time noone had looked at it closely (we had other specimens, true D. choprae for the morphological data). Time passed on. This was one species that Fang never worked on, but which obviously was somewhat different from the other samples of D. choprae, and I decided to give it a go in the Spring of 2012. The manuscript was already in hand as I again met Ralf in Belgium and we spoke about past achievements and plans for the future. As he had more of the danios from Putao from a later trip, and more D. choprae, he insisted that I include this material, and so it was. The paper had to be done from almost scratch but Ralf’s material certainly improved a lot on the description and conclusions. The description of Danio flagrans, the northern glowlight danio, eventually appeared in late 2012, 14 years after its discovery (Kullander, 2012). Incidentally, it is my first own danio paper, and it was fun to do. It was enjoyable in particular, because Danio flagrans and its sister species Danio choprae do not differ only in colour (in fact they are very similar in colours), but also present some very solid morphometric and meristic differences. I am otherwise much too used to cichlid species that differ by just some pigment spot. Danio flagrans has a shorter anal fin, with less fin-rays, and longer caudal peduncle compared to Danio choprae. Perhaps this relates to their environment. Danio choprae lives more to the south, near Myitkyina, and in warmer habitats; Danio flagrans in cool hillstreams. Beware that these species may not be correctly identified in the shops. Danio choprae, the glowlight danio may appear in the market as northern glowlights, a more expensive fish. I know, three of the false northerns are swimming in a tank in my garage. These changelings are beautiful fish decorated with orange stripes. Unfortunately, they never stay still, but are constantly on the move, and they move fast, so a good view of them remains an illusion of expectation. This brings me, by association, to the conclusion of this post: Besides lights in the windows, there is one more resource to overcome winter gloom. An aquarium with beautiful fishes (all fish are beautiful). Always something to see, to learn, to enjoy.

References

Fang, F., M. Norén, T.Y. Liao, M. Källersjö & S.O. Kullander. 2009. Molecular phylogenetic interrelationships of the South Asian cyprinid genera Danio, Devario and Microrasbora (Teleostei, Cyprinidae, Danioninae). Zoologica Scripta, 38: 237-256.

Kullander, S.O. 2012. Description of Danio flagrans, and redescription of D. choprae, two closely related species from the Ayeyarwaddy River drainage in northern Myanmar (Teleostei: Cyprinidae). Ichthyological Exploration of Freshwaters 23: 245-262. Open Access PDF from Verlag Dr. Friedrich Pfeil.

Kullander, S.O. & R. Britz. 2002. Revision of the family Badidae (Teleostei: Perciformes), with description of a new genus and ten new species. Ichthyological Exploration of Freshwaters, 13: 295-372.

Kullander, S.O. & F. Fang. 2005. Two new species of Puntius from northern Myanmar (Teleostei: Cyprinidae). Copeia, 2005: 290-302. Open Access PDF.

Photos: Sven O Kullander, CC-BY-NC