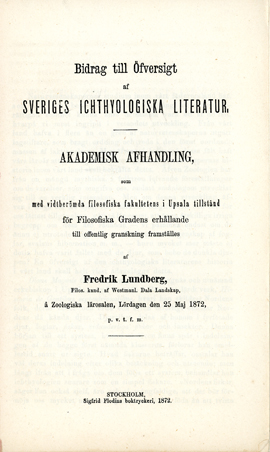

There is a little book – a dissertation actually – that lists every Swedish publication on fishes. Published in 1872 it of course had some advantage over any similar project to be raised today, but nevertheless it is a commendable work. It was presented as a doctoral dissertation at Uppsala University by Fredrik Lundberg, and comprises 18 pages of introduction and 56 pages of bibliography. The author, Lundberg, vanished in the shadows of time, at least this dissertation is the only evidence I can find of the person. Both Fredrik (currently first name of 95962 men and 2 women in Sweden) and Lundberg (currently last names of 21123 persons, first name of 3 men and one woman in Sweden) are common names in Sweden. Well, even if people may be interesting, it is a person’s work that counts, so I am basically content. Lundberg’s dissertation is important for tracking the history of ichthyology in Sweden, and for me it was the key to finding a rare publication that practically every other ichthyologist in Sweden refused to cite.

There is a little book – a dissertation actually – that lists every Swedish publication on fishes. Published in 1872 it of course had some advantage over any similar project to be raised today, but nevertheless it is a commendable work. It was presented as a doctoral dissertation at Uppsala University by Fredrik Lundberg, and comprises 18 pages of introduction and 56 pages of bibliography. The author, Lundberg, vanished in the shadows of time, at least this dissertation is the only evidence I can find of the person. Both Fredrik (currently first name of 95962 men and 2 women in Sweden) and Lundberg (currently last names of 21123 persons, first name of 3 men and one woman in Sweden) are common names in Sweden. Well, even if people may be interesting, it is a person’s work that counts, so I am basically content. Lundberg’s dissertation is important for tracking the history of ichthyology in Sweden, and for me it was the key to finding a rare publication that practically every other ichthyologist in Sweden refused to cite.

On page 29 Lundberg cites an article “Om Ichthyologien och Beskrifning öfver några nya Fiskarter af Samkäksslägtet Syngnathus. Af G. I. Billberg, (Linn. Samf. Handl. 1832, p. 47-55 m. 1 col. pl. Sthlm 1833).” The article was evidently in a journal with the name encrypted. It was somehow resolved as Linnéska Samfundets Handlingar (Proceedings ot the Linnéan Society). Decryption of journal name abbreviations is not for the impatient and weakhearted; luckily this tradition has been abolished in favor of very short names easy to mix up or very long names difficult to remember. As I could not find any further mention of pipefish species named by Billberg in other Swedish fish literature, or elsewhere – they were not incorporated into the Catalog of Fishes until in February 2016 – it was too good bait to resist.

This was in 2004 and although libraries were already restricting access to their older publications, online antiquariats were few. A copy of the particular journal issue could be found, however, in a Real Life antiquariat in downtown Stockholm for a considerable price. A second copy was lent to me by Professor Bertil Nordenstam, then at the Phanerogamic Botany department of the Swedish Museum of Natural History. The author, it turned out, was mainly a botanist or horticulturist, and the publication contains images and descriptions of plants

“Om Ichthyologien …”, indeed, the whole issue of the Linnéska Samfundets Handlingar (the first and only), and not least the curious author, were found to be extraordinary in many ways, good and bad. It was a discovery of a forgotten milestone in Swedish natural science that certainly needed attention. Billberg, a lawyer and judge, botanist and natural historian by devotion, and funder of of the Linnéska Samfundet, attempted to present a new classification of fishes, and also, a man of classical education more than biological, had a lot to say about other people’s scientific names on fishes. The publication is sprinkled with new names on all kinds of fishes, family names, generic names, species names, but practically all of them needed to be evaluated in relation to the International Code of Zoological Nomenclature, and most of the fragmentary literature references pointed to sources not so easy to find in 2004 as they are now. So it wasn’t just the exciting discovery of three overlooked pipefishes. It was a true Pandora’s box, or can of worms, can of names.

Billberg proposed five new family names, only one of which survives as it is anolder homonym (Diodontidae). He mentions 61 genera of fishes, 41 of them listed only by name; out of 20 “new” generic names, none is valid. He he lists 31 species of fishes.; out of 28 “new” species names, one is potentially valid and a species inquirenda. Hardly anything in the taxonomy is justified by anything oyher than imprecise references. It turns out that Billberg probably based the whole paper on only one or two earlier works, by La Cepède (1798), and Cuvier (1817), with the outstanding exception of the description of three new pipefish species. The pipefish descriptions were based evidently only on three drawings made by Johan Wilhelm Palmstruch in 1806, probably from living specimens. So Billberg could have written his paper having examined zero fish, read two already long outdated books, and counted fin rays on three drawings. Of couse, the three new pipefish species are also junior synonyms.

Plate in Billberg (1833) showing new pipefish species 1, Syngnathus pustulatus (male Syngnathus typhle), 2 Syngnathus virens (female Syngnathus typhle), and 3 Syngnathus palmstruchii (Entelurus aequoreus)

What man had set his footprint so deep in the mud that it could not be retracted? In short, Gustaf Johan Billberg was born Karlskrona in Blekinge, southern Sweden in 1772. He studied law in Lund University and got a position as auditor in Stockholm in 1793. He took a similar position in Visby on the island of Gotland in 1798, but returned to Stockholm in 1808 and held various administrative and juridical positions there, mainly as a judge, until 1840. He became a member of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences in 1817, and corresponded with Linnaeus’s successor in Uppsala, Carl Per Thunberg, but he never had a formal education in natural sciences. He was a collector, with large entomological collections, and took particular interest in botany and economic botany. If he had not been caught in some controversy between the Academy and Uppsala University, perhaps he could have developed a career as a botanist. Instead he devoted his fortune and time to publishing more or less unfinished works that along with other events drove him to bancrupcy. Some of these publications are significant, like his two issues of the work Ekonomisk botanik (Economic Botany) and a few parts of the book series Svensk botanik (Swedish Botany) and Svensk zoologi (Swedish Zoology), the latter in particular a pioneering work with descriptive text and hand coloured plates of Swedish animals. The society that he initiated, Linnéska Samfundet, was equally commendable, but quickly dissipated. The society produced just one issue of its proceedings, all articles in it written by Billberg, and apparently biologists showed no strong interest in the society. Billberg did make a lasting contribution, however, in developing one of the green areas in the heart of Stockholm, Humlegården. There he organised a Linnaeus Park, including a hilly flowerbed area still present today and known as Flora’s hill, named for his daughter Flora Mildehjert. Boethius (1924) wrote a detailed biography of Billberg.

Billberg’s enthusiam for natural sciences, particularly plants and animals, carried him high up among the clouds, and let him fall hard. When he died in the winter of 1844 he was broke and ill. By contrast, his brother Johan, without interest in natural history was ennobled af Billbergh in 1826. On the other hand Gustaf Johan brought up 9 children and one of them, Alfred, a medical doctor, became a well renowned pioneer in psychiatric medicine.

Years passed, however, as they tend to. “Om Ichthyologien…” remained a resting treasure as many other projects called for attention. The idea remained, however, to present an analysis of Billberg’s paper, and particularly to call attention to the existence of three forgotten species description contained in it. I started, stopped, and started, compiling names and checking literature sources. At first I thought that a tabular presentation would be enough, but no, too much needed to be said about this work. Eventually, after a senseless, sleepless final effort in early 2015 could I deliver a manuscript for submission. But it should take long time to see it in print. The main problem was obviously finding a reviewer. At last things could be resolved and in October 2015 there was an accepted manuscript. I will spare you all the details why its publication (Kullander, 2016) was then delayed till January 2016.

As you can read the whole analysis of Billberg’s fish names here, thanks to Open Access and somebody paying for that, this is not the place for reiterating detail that is already there. If you want a different context you can also find much of the information in the Catalog of Fishes.

Billberg’s many publications drew considerable criticism already during his lifetime, especially his unsuccessful habit of reforming the Swedish names on animals and plants. Billberg’s fish paper was ignored by all Swedish ichthyologists first probably because he was not accepted by the contemporary academics, and later because he simply fell out of memory. Several large volumes on Scandinavian fishes were published in the period 1836-1893.

Billberg has been called enthusiast, dilettante, and many other things, but on the positive side he was really an educator at heart, and it is difficult to criticize a person following a vocation to investigate things and try to make the world a better place, no matter how awkward the result then can be. The history of science is full of worse people. The worst that Billberg did was to put newly constructed names on plants and animals. That is something that many of us do …. Perhaps the review of his fish names can contribute to make him remembered more for his good aspirations than his formal failures. And serve to remind one always to be very careful when playing with names.

References

Billberg, G.J. 1833. Om ichthyologien och beskrifning öfver några nya fiskarter af samkäksslägtet Syngnathus. Linnéska

samfundets handlingar, 1: 47–55. [at Internet Archive]

Boethius, B. 1924. Gustaf Johan Billberg. Svenskt biografiskt lexikon, 4, urn:sbl:18212.

Cuvier, [G.] 1816. Le Règne animal distribué d’apres son organisation, pour servir de base à l’histoire naturelle des animaux et d’introduction à l’anatomie comparée. Tome II. Déterville, Paris, xviij + 532 pp.

Kullander, S. O. 2016. G. J. Billberg’s (1833) ‘On the Ichthyology, and description of some new fish species of the pipefish genus Syngnathus. Zootaxa, 3066:101–124.[at Zootaxa]

La Cepède, [B.G.] 1798. Histoire naturelle des poissons. Tome premier. Plassan, Paris, cxlvij + 532 pp.

Lundberg, F. 1872. Bidrag till öfversigt af Sveriges Ichthyologiska literatur. Akademisk afhandling med vidtberömda filosofiska fakultetens i Upsala tillstånd för Filosofiska Gradens erhållande till offentlig granskning framställes af Fredrik Lundberg Filos. kand. af Westmanl. Dala Landskap, å Zoologiska lärosalen, Lördagen den 25 Maj 1872, p.v. t. f. m. Stockholm Sigfrid Flodins boktryckeri. xviii+52 pp.

I was comfortably seated in the sofa, in a conversation about books bad or good, literature that is. My eyes crawled for cues along the backs of books in the sunlit bookshelf across the room, eventually steadying on a 15 volumes work from the early 1960s that presents the animal kingdom in a phylogenetic sequence and providing some food for thought. It is in Swedish and intentionally popular but probably too advanced for readers in the 21st Century. Departing from the traditional Brehm, Djurens värld edited by

I was comfortably seated in the sofa, in a conversation about books bad or good, literature that is. My eyes crawled for cues along the backs of books in the sunlit bookshelf across the room, eventually steadying on a 15 volumes work from the early 1960s that presents the animal kingdom in a phylogenetic sequence and providing some food for thought. It is in Swedish and intentionally popular but probably too advanced for readers in the 21st Century. Departing from the traditional Brehm, Djurens värld edited by