The discussion recently in the iczn-list (yes, an e-mail discussion about matters related to the International Code of Zoological Nomenclature) has been heated by vandals. That is, strong feelings have been expressed about vandals in taxonomy.

The reason there are vandals is because there is a definite ethically correct behaviour in matters nomenclature, and because Zoological Nomenclature is one of the oldest and best functioning globally endorsed anarchistic systems in history. There are rules, but it is up to the users of names to follow the rules. Strangely, it works most of the time. Vandals are those that do not follow the community rules, but abuse the system, taking advantages they should not have. Abusing freedom is inviting control. And that may not in the end make the world better.

Taxonomic vandals are of a few different kinds (my classification).

(1) Hooligans. These folks are absolute nuts about publishing new names. Whether their species exist or not is irrelevant to them. In the most recent example discussed, author A published a description of species B, and then copy pasted the same description for species C. This seems to be a pest among herpetologists and malacologists.

(2) Nominomaniacs. Nominomania is the obsession with scientific names, which in itself is possibly harmless, but there are bad guys (men only) here. Nominomaniacs of the bad kind eat homonyms like caterpillars chew leaves. They make new names for every junior homonym they can find, without checking up the organism, or whether a specialist may not already be concerned with these homonyms. Nominomaniacs are frequently authors of names outside their group of speciality, if they have any.

(3) Mihi-itchers. These people cannot leave any variation in nature without a name. Somehow they also frequently happen to publish a first name for the same species as a colleague is working on. A special case of advanced mihi itch is the Phylocode where you have to put a new name on every clade you may happen to find (I am provocative here). Mihi-itchers, like sneakers, lurk among the posters at conferences, take photos, and save many days of work efficiently and conveniently.

(4) Sneakers. Whenever a specialist has established a descriptive standard for a group, sneakers will copy paste his/her descriptions, make a few changes and apply it on their own species, preferably ones that are already under study by a specialist. Aquarium hobbyists do this, because they have no training in ichthyology and do not know what they are looking at. Students may be tempted to take this easy road as well.

They are not many, maybe 10 or so in the world at any given time, but they upset people considerably. You know these persons because they as a rule do not participate in scientific meetings, usually run their own journal or exploit weaknesses in journals that do not have a strong editorial control, have no research funding, always have specimens from places where nobody else gets a permit to collect, etc.

Why is it so? Taxonomy has no impact factor of interest to society or funding, so why bother?. Psychological factors aside, Nomenclature has one major problem called authorship. It is more or less obligatory to put the name of the person(s) who described a species after its scientific name.

Consider Dicrossus filamentosus (Ladiges, 1958).

Ladiges did a not very good one on this species; it was published as a sort of preliminary description in an aquarium magazine, based on two very dead aquarium specimens without locality, described by a non-specialist. It is a distinctive species, so no real harm done, and there were no specialists on South American cichlids available at the time. Most of the relevant information about the species, including geographical provenance only appeared with my redescription in 1978 (a student paper, not so advanced, but still helpful). Ladiges will forever be cited as the author of the species, although he did not do anything useful with it. Later workers will be more helped by Kullander (1978), which is practically never cited.

I take this particular example to show that even if the scientific basis for a description is very, very weak, it frequently gives more citation and more food for the ego than any other work on that species later. Confounding authorship associated with scientific names with scientific citation is bad in itself, but it also certainly is a major driving force in taxonomic vandalism.

In science elsewhere, bad or boring (like taxonomic papers) papers never get cited again, and their authors are peacefully brought to oblivion. The only way outside taxonomy to obtain a reputation is to work hard to do something useful.

The end result is that we have an extra number of useless names that specialists must consider for the rest of their professional career; we have lots of duplicate work, blocked access to relevant specimens, type specimens deposited in private collections unavailable to specialists, loss of trust in the profession, and in the end uneasiness and unwillingness among professionals to communicate openly about their work.

The Code of Ethics in the International Code of Zoological Nomenclature, is very straightforward about what behaviour is expected from those making nomenclatural statements. In the case of my lab, we work on the systematics of danionine cyprinid fishes, the genus Puntius, South American cichlids, and in collaboration the fishes of Myanmar and Paraguay. I am not expected to check with others whenever I have a new species in these groups, and there are many of them. Everyone knows that we work on these fishes (or would have known if the Newsletter had existed; see previous blog). You do not have to check with me if you are thinking of describing a new species of goby from the Seychelles. But if I would find a new goby from the Seychelles I would need to check if somebody else might be working on it. And anyone working on any of the above groups is expected to check with me first, and with other colleagues that have known interests in the same area.

Two weeks ago I received a new species of fish; concluding it was new and interesting enough to describe, I checked with another specialist on that family two days ago, and it turned out he has the same species from the same place, so we have to make an informed and friendly decision how to go about it.

The job of the taxonomist is to a large extent to give scientific names to organisms. It is a little reward on top to the sometimes repetitive analytical work. Of course, we all get a little of the mihi itch (mihi means mine; this itch is about appending one’s name to species names), but it easily cured. However, among the many, many scientists in Ichthyology that I respect, all of them were always more concerned with the analysis than with their author status, and more concerned with having a publication that people want to read and use, than having their names cited. That is what science is about.

So, what should we do? Outlaw some people or journals? Permit only certain journals to publish nomenclatural acts? Apply to the Commission for suppression of every name not considered appropriate for whatever reason? Ignore the names published by vandals?

In the end, who judges vandalism? When am I a 100% vandal, or a 10% vandal or perfectly non-vandal, in the eyes of 5%, 50% or 100% of my colleagues? Is this about people or about the Code? Who is more mihi-itchy at the end of the day, the vandal or the vandalised? Ethics cannot be ruled, it can only be demonstrated. So, I would prefer to leave the system open, with the very slight disadvantages it may have. But the Code of Ethics of the International Code of Zoological Nomenclature maybe should be more widely known.

What does the Zoological Code say then. I quote the most relevant parts of the Code of Ethics from the ICZN website:

1. Authors proposing new names should observe the following principles …

2. A zoologist should not publish a new name if he or she has reason to believe that another person has already recognized the same taxon and intends to establish a name for it (or that the taxon is to be named in a posthumous work). A zoologist in such a position should communicate with the other person (or their representatives) and only feel free to establish a new name if that person has failed to do so in a reasonable period (not less than a year).

3. A zoologist should not publish a new replacement name (a nomen novum) or other substitute name for a junior homonym when the author of the latter is alive; that author should be informed of the homonymy and be allowed a reasonable time (at least a year) in which to establish a substitute name.

4. No author should propose a name that, to his or her knowledge or reasonable belief, would be likely to give offence on any grounds.

5. Intemperate language should not be used in any discussion or writing which involves zoological nomenclature, and all debates should be conducted in a courteous and friendly manner.

6. Editors and others responsible for the publication of zoological papers should avoid publishing any material which appears to them to contain a breach of the above principles.

Some interesting examples where opinions are strong:

Adamas Huber 1979 replaced by Fenerbahce Özdikmen et al. 2006

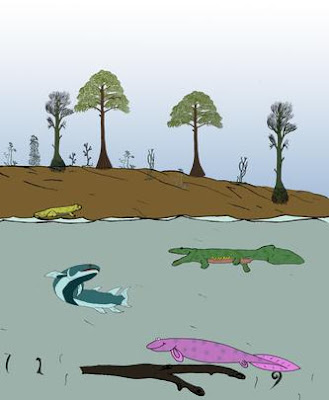

What herpetologists talk about