Marvel at those majestic buildings harbouring the biological heritage of nations. Natural history museums. Other research collections. The millions by the thousands of corpses and skins, leaves and stems, rocks and gems. Wondering about the shadows cast from time to time across the occasional window lit night after night. Dinosaur or Man, ghost or guard? Strolling through the galleries, what’s behind all those doors that remain locked? More treasures or just the junk? It is not so straightforward to explain what goes on in research collections, and difficult to imagine up. But for sure, there are collections safe in store rooms. And there are the scientists and the collection care staff. And, of course, some administrators. There is always something you can see of collections, and there are the reports, the scientific and not so scientific papers and web presentations, so nothing is really hidden.

But have you ever had a glimpse of a professional abode therein? Is it roomy or squeezy, white-walled or padded with trophy heads? Is there always a Larson in lieu of less intelligible art? Coke or coffee? White coats or tees? When I was so much younger than today I had an idea but not all the imagination. Then, indeed a long, long time ago, I was led by Gordon Howes through a maze of corridors and through the one locked door after the other to arrive at the magical heart of the fish division of the British Museum (Natural History) – now known by a lesser name – and there it was, the air, perfused by alcohol fumes, the books, the microscope steady on the bench, and the uncmfrtbl (so they pronounce it) chair, the tall windows and the big men, books, books, and reprints, reprints, greasy jars, soft dead fish with their autographs helped to them by the wisest of ichthyologists, Günther, Boulenger, Regan. Enchanted, it was a revelation of what life ahead was to be like. And now it is all gone, all the smell, the patina, the deoxygenated atmosphere, the dirty windows, and the kind of yellow Wild microscopes. Everything is new and shining and the nervousness – or was there any – about that spark that would send the alcohol to flames and the building to a cloud of dust, it is no longer there, fire regulations everywhere. And all the other museums are going modern as well. Actually I like the new style too – the facelift is an expression of value and respect for the scientists and their working material. As I much later came to my museum in Stockholm, it was just like that, dirty, dark, dull, and a bit dumb. Now it is full of fresh fish, gas driven chair seats, top-end computers, motorized microscopes, and all the papers are becoming pdfs. As I started on this essay, it was because I were soon to move to new quarters, smaller, newer, and the present, acquired coziness would be part of history. I have been in this office since … 1980? and it was upgraded only once with a little paint and new floor. Since nothing of the classical ichthyological laboratories of the overladen, all-inclusive kind was saved elsewhere (or ?… challenge me!) I decided to photo-freeze a bit of ichthyological history, speaking for many a demolished scientist’s office as new times have moved in. End of the commercials, take a seat and enjoy my research workshop, something like six by three meters and the ceiling truly up in the sky almost. If you ever wondered what a classical fish researcher lab looked like a late afternoon in the winter of 2012, here are all the details (well, a good part of them). If you came upon this text my daily practice unbeknownst, you may wish a confirmation that I am a fish systematist – there it is.

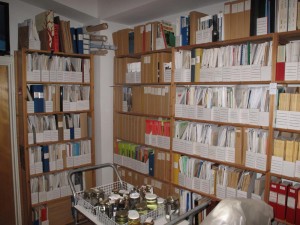

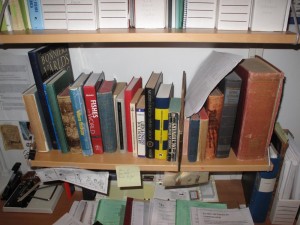

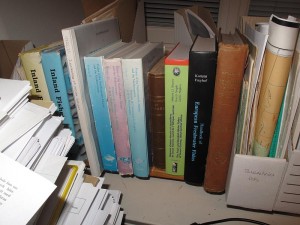

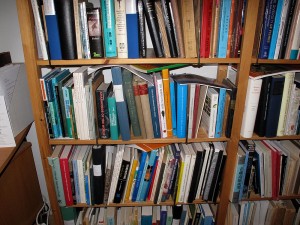

What you see to left and right, front and back, upp the walls and on cabinets and desks – are books and reprints. A sine qua non for life and science alike. The books and reprints in my office are those that are required for ongoing projects and such that are needed for various office tasks such as identifying fish for the public, colleagues and whoever calls. Books that are needed for finding information fast. Highlights are of course the Scott Liddell Greek lexicon, and Erik Wikén’s fabulous Latin for botanists and zoologists (Latin för zoologer och botaniker), in Swedish. I certainly need that copy of Artedi all the time, and right now I am trying to speed learn about Tanganyika cichlids from Günther and Boulenger to Poll and a massmess of molecular writings. If the hand library fails, topping it is the department library which has one of the best collections of fish books, journals, and reprints. Would it not suffice, there are of course AnimalBase and the Biodiversity Heritage Library.

Reprints used to be the blood running through the veins of ichthyology, and here they are still running across the walls. Authors always procured a hundred or two of each of their publications and distributed them for free. The point with reprints was that one would not need to subscribe to a journal, and one would not need to page through a whole volume of articles to find tiny scraps of information. Consequently, every footnote and misspelling was elegantly served by reprints, and so taxonomist could indulge in nitpicking ad libitum. It is only in taxonomy, in all of scientific publishing, that people comment on each other’s misprints, yes? The pdf option and Open Access have now killed the reprint collecting efficiently, but that’s all right as long as the printing errors remain …

It takes two (actually three) computers to keep things running, and all data are saved in paper format in three filing cabinets, a dossier for every species and dossiers for other data. Two microscopes may seem overkill, but one is dedicated for photography and one for fish examinations. So one can work in parallel. You will not find many jars in the study, because of fire regulations. Only lesser amounts of ethanol are permitted in offices those days, and the jars needed for the time being are assembled in trays on a cart for convenient transport back to the store rooms.

Stop the presses! Miraculously, this installation still remains. By a lucky chance the move was cancelled at the very last minute, and consequently change is not going to play with my order. Not now. I am happy. What about you? And, what’s your office like?

Photos: Sven Kullander, CC-BY-NC